Jan Rocek

Jan Roček. (Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch)

JAN ROČEK: A LIFE PROFILE

CHILDHOOD AND FAMILY

Jan Roček was born in 1924, in Prague, and lived with his mother, father, and younger sister, Helga (born in 1929) in a suburb called Strašnice. “My mother was from the German speaking part of the country, so we spoke German at home a lot until 1933 when Hitler came to power. My father forbade a word of German to be spoken, which was very hard on my mother who never learned Czech very well.” Jan has fond memories of playing Ping-Pong with his best friend, a Gentile boy who lived in the same building. He had other friends in the neighborhood, including a German boy and a Jewish girl; and in school he had mostly non-Jewish friends.

Jan was never a religious person. His family was not observant, and his father was obviously an Atheist, although he never explicitly revealed his beliefs, wanting Jan to form his own without bias. “My father left the congregation when he came back from WWI and found out that his mother, who was quite religious, was no longer alive.” The only Jewish observance that Jan remembers in his family home was the Yahrzeit of his maternal grandfather. “My mother would light a little chalice with oil and a floating wick. We had Christmas trees until my father discovered that it was a Germanic custom, but we still celebrated Christmas.”

He fell in love with chemistry at age 16 after taking a course at a chemical school, organized by the Jewish Community after Jews were expelled from public school; it was the first time he had an academic interest. “It immediately fascinated me. Somehow I felt that chemistry gave me an understanding of the structure of the world. We did analytical chemistry; it was like detective work to identify the compounds and elements. I decided from that moment on that I definitely wanted to be a chemist.”

OCCUPATION & DEPORTATION

“I remember quite vividly the day when the Germans marched in. My father told me, ‘The Germans will lose the war, but they will succeed in killing all the Jews.’”

Jan’s father and uncle co-owned a small paint factory where they continued working, under an imposed German supervisor, until the day they were deported. After 1940, Jews were no longer allowed to attend public school, and so Jan worked in his father’s factory for a short time, until his father found him an apprenticeship at a machine shop. This experience proved to be crucial for Jan a few years later in Auschwitz, as it meant he felt able to claim that he was a metalworker. “It probably saved my life later on in Auschwitz because I said I was a lathe operator even though I had only worked on lathes five days during my entire life.”

When the transports from Prague began, the laboratory at Jan’s [former] school was turned into a dye shop, a service that quickly became in high demand. Each deportee was permitted to bring about 110 pounds of personal belongings, including clothing and bedding. To avoid having white sheets that looked dirty (access to laundry facilities was, like many details, a complete unknown), people brought their linens to the shop to have them dyed dark blue or brown. Because there was only three days advance notice of deportation, there was very little time to boil-dye the linens and dry and iron them, so Jan and his cohorts were kept very busy.

On May 12, 1942, Jan, his sister, and their parents were notified of their deportation. Three days later they took the streetcar from Strašnice to the gathering place in Prague. From there, the Roček family and other Jews were ordered onto a train to Bohušovice. Upon arrival Jan, his family, and the other prisoners walked the two miles to Terezín. “It so just happened that my best friend, Arnošt Reiser, was on the same transport as us, and because our names were close in the alphabet we were situated practically next to each other.”

ARRIVING AT TEREZÍN

Jan Roček holds the key to the house he lived in while a prisoner in Terezín (Address Q 708). The key was given to him during his last visit to Terezin in 2009 by the current occupant. During WWII, the door which the key would have opened was permanently closed because it faced a park (Brunnenpark) that was reserved for the Germans. Jan and his friends entered through the adjacent house, L 218. (Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch)

Jan said that when they arrived at Terezín, it was actually a bit of a relief. “There was tremendous tension whenever there were these transport notices sent out. We were always on tenterhooks, waiting.”

Jan’s family was very fortunate. The first doctor who went to Terezín was Jan’s cousin, Erich Klapp, who became a member of the Ältestenrat, the Jewish Council of Elders at Terezín. Klapp was able to protect Jan and his family until the fall of 1944, when he was sent to Auschwitz and killed. “That’s why we were able to stay in Terezín for so long,” said Jan, “A lot of other people in the transport continued to ‘The East,’ as it was called.”

Initially, Jan and his father lived in the Sudeten barracks, and his mother and sister were housed in the women’s barracks. Jan recalls a huge hall, where about 200 people slept in three-level bunk beds. The family members were not permitted to freely visit each other because there was still a civilian population in the town of Terezín.

In the beginning, everybody worked in the hundertschaft – groups of 100 people – doing menial labor, whatever was needed. “Nobody at Terezín worked in a terribly exhausting fashion,” said Jan.

Jan was in the barracks for a while, until he fell ill with a middle-ear infection. He was put in the local infirmary, and subsequently was operated on in the hospital; a Dr. Tarjan performed a skull trepanation.

WORKING AT TEREZÍN

After recovering from surgery, Jan was assigned to work in a kitchen. The kitchen was the best place for a prisoner to work, as it afforded access to additional food, and everybody was hungry. Jan’s job was physically demanding, carrying heavy loads of coal from the basement up to the kitchen. Unfortunately, after a few days he realized he was not strong enough to continue this strenuous work, so he had to give up.

His next job at Terezín was in agriculture, working in a vegetable field. One day, as he was toting material in a wheelbarrow, he walked past a building that was now operating as a laboratory. Looking in the window, Jan recognized the same chemistry equipment he had used in the course he took in Prague. “So, I walked in and talked to the director, and expressed an interest in working there. He tested me on the spot, and was impressed by my knowledge of chemistry.” The lab director tried to get Jan reassigned there. Even though his request was turned down, the director gave Jan permission to come after his own working hours to help out. Jan said he enjoyed that very much.

One day, Jan helped unpack a big shipment of chemicals from Prague. “At that time, every bottle of pure chemical with its label was just a delight to look at and to handle it.” Ultimately, the director was able to get Jan transferred to work in the lab, as well as one of Jan’s former classmates. “One day I met my friend from the chemistry course, Arnošt Reiser, and brought him to the lab and introduced him. And he was then working in the lab, too, so we were together. Later on his sister joined us too, so we had a nice group there.” They worked there together until Jan’s transport to Auschwitz.

MEETING EVA

Jan met his wife Eva [Porges] at Terezín when they volunteered to help elderly prisoners carry their heavy luggage during the transports in May 1944. Eva, who was 17 at the time, had some luggage that was too heavy to carry by herself, so she asked Jan for help.

“I was brought up by my father in old fashioned traditional ways, so I introduced myself with the words, ‘If you permit me to introduce myself, my name is so and so.’ Eva said that I was barefoot and clicked my heels as I bowed, and she says she fell in love with me at that moment.”

After that, the two did not see each other for a while, until one day Eva was with a friend and spotted Jan. “We talked and talked, and the friend excused herself and left us alone. I had a typewritten collection of poetry by the Russian poets [Boris] Pasternak and [Sergei] Yesenin, and I lent her that.” The two started seeing each other regularly, and both were inexperienced in romantic affairs. “One day I decided to kiss her, and she went crying home about the terrible thing she had committed. Her mother had to assure her that it was perfectly alright.”

AUSCHWITZ

Jan was deported to Auschwitz on September 28, 1944. He arrived to a cacophony of yelling and shouting, prison guards brandishing sticks, and prisoners in striped uniforms. Jan and the other prisoners on his transport were forced to go into a line toward a man who Jan later surmised was Josef Mengele. “He stood there and looked at people, and pointed each toward one way or the other way, without asking any questions.”

It was nighttime when Jan arrived, and he remembers seeing the barbed wire fences. “I saw the big chimneys with fires there, and I assumed they were factories. There was a rumor that people died in these factories, from working in the bad conditions.”

Jan and his fellow prisoners were taken to a large room where they were ordered to undress, and allowed to keep only their shoes and eyeglasses. “They shaved our whole body, and smeared us with stinging disinfectant.” The prisoners were given clothing: a shirt, a vest, a jacket, pants, and underwear made out of Jewish prayer shawls. “The underpants were specifically made from tallit to be very offensive. It didn’t bother me so much, but for religious people it was extremely offensive,” he said.

Jan and the other prisoners were led to the barracks, which had been a large horse stable. The conditions were incredibly crowded, holding about 1,000 people. “The only way we could to try to sleep was to sit on the floor with your legs outstretched, and the person who sat next to you leaned against you, and so on, in long rows.” Later, Jan was in another barrack where there were bunk beds, though it was equally overcrowded. “There were so many people that when we slept, everybody had to turn over at the same time, to be synchronized.”

Food for the prisoners came in large vats. “It was a so-called soup, there was no solid food. There was a big heap of old pots and chamber pots and washbasins, and several people had to share one washbasin of food together. There were no spoons, so you just had to eat like an animal. We were not allowed to take our shoes up to the bunk. On the other hand, we were afraid that somebody would steal them,” he recalled. Jan remembers being punished for having his shoes in his bunk. “The Kapo [a prisoner who was assigned by the SS guards to supervise] allowed me to take off my glasses before he slapped me, so I didn’t lose my glasses at least.”

Jan remained at Auschwitz for one month. He remembers that his transport was scheduled to leave on October 27, the day before the Czechoslovak national independence day. “We heard that months before, on the date of the first Czech president’s birthday, the Nazis liquidated the so-called family camp, and all the Czechs were gassed on that particular day. So we were very apprehensive that they would again do something like that on a Czech holiday.”

Representatives from German factories came regularly to recruit some of the prisoners for various types of labor. Jan claimed to be a skilled lathe operator, and was selected to go to Meuselwitz to work as a metalworker in a munitions factory.

THE LABOR CAMP

In Jan’s assessment, Meuselwitz was a big improvement over Auschwitz. Each prisoner had his own space on a narrow triple bunk bed, with a straw mattress and a thin grey military blanket. Another improvement over Auschwitz: the inmates had their own bowl and spoon. Mornings they got some ersatz coffee, and in the evening, soup and a small loaf of bread for three people. Jan and two of his bunkmates had an elaborate procedure to split the portion equitably. “I had a knife which I made from a broken saw blade in the factory, so one person cut the bread, and then another one had the first choice of the pieces, and then we alternated, so in our case, it was very fairly done.” Jan describes his bunkmates as a nice group, including Jan’s friend from his room in Terezín, a very bright 16-year-old boy named Vilém Pollak, and Jan Sander, a nephew of a former Jewish minister in the pre-war Czechoslovak government.

Jan’s work on the lathe was a very simple job, devising a small cylinder that held bullets, but the workdays were very long. “The shifts were 12 hours, with 1 hour of rest in the middle. I fell asleep at the lathe sometimes, and the cutting tool got broken, but I learned how to fix it myself.”

While Jan worked in the factory, there were regular air raids both during the day and at night. He says, “We assumed that the Allies were bombing only in large cities. We were always very happy when there were air raids. They sent us back to the camp, while the Germans took cover in cellars under the factory. It turned out that we were wrong.”

During one of these air raids, a bomb fell just opposite of Jan’s barrack. “The wall fell in, but fortunately, the roof held. I was not that scared. But just purely rationally, I would climb under the bunk bed, assuming it would protect me.” Jan recalls that prisoners from the women’s camp had panicked during an air raid, ran past the gate and into the woods, and many of them were killed by Allied bombs. Another bomb hit the cellar and killed a lot of Germans who were taking cover in the bunker under the factory.

LIBERATION

In May, 1945, word in the camp spread that the Americans would be there in two days. However, the American troops were in the midst of fighting the German resistance, and so their arrival was delayed. “That gave them time to load us onto railroad cars. The cars were full of coal briquettes, and so we were ordered to empty the contents onto the platform and get into the emptied open railroad cars.”

Jan took his few belongings with him: blanket, bowl, and a German bible, which he had found while digging unexploded bombs from the ground in a nearby town. Jan had volunteered for this dangerous work because an extra slice of bread was offered as a reward. “I didn’t care whether I’d be killed or not, at this point, but I’d be willing to do anything for a slice of bread.”

Jan and his fellow inmates spent five days on these open railroad cars, headed away from the Front, without any food except for some turnips they were able to scavenge along the way when their train stopped next to a train with a load of turnips. With about 100 people in each car, conditions were crowded. “There was not enough space to sit down, so most of us were standing. There was a group of Jews from Poland, and they occupied the few places for sitting, alternating amongst themselves so the rest of us didn’t have the chance to get a seat.”

The inmates were permitted to get out of the train cars at Kraslice, a town on the former Czech-Slovak border. A German military train approached on the other track, with dive-bombers in pursuit. “They bombed the Germans, and also some cars on our train by mistake, killing some people. The townspeople decided that it was us who attracted the bombers, and they asked the SS to take us away.”

Jan and a few others made a feeble attempt to escape. They were caught by some local German police, and detained in a makeshift jail. “I remember we were terribly hungry, and there were young boys around who tossed raw potato peels at us and found it very entertaining that we were eating them.”

Jan was returned to the SS and, from that point on, he and the other inmates were forcibly marched on foot for days. Jan remembers his friend and bunkmate, Vilém Pollak, a very bright younger boy with whom Jan had read philosophy books. Jan had discarded his treasured bible, so as not to be weighed down with it, which angered Vilém, who picked it up. “That was when I saw him, the last time; I think he got very sick and was never heard of again.”

“There was nothing in the beginning, no food, no shelter,” he said. “We were sleeping outdoors in the Ore Mountain Range (Krušné hory) and I got frostbite. Later we got some food and slept in barns rather than out in the open, but by that time I was in terrible shape.”

It wasn’t only Jan whose health was in severely compromised. “There was a father and son that managed to get through. The two were sleeping next to me in the barn, and in the morning, both were dead, died in their sleep from total exhaustion. They had a few potatoes with them, so I took them and ate them.”

His friend, the actor Karel Švenk, was also too weak to continue to march. “They found him hiding in the straw and they shot him.”

Jan was also completely exhausted by this point. “I just didn’t care anymore, so I just simply didn’t get up. The Germans came and poured some water in my nose, and saw that I was not dead. I expected them to shoot me but I couldn’t care less at that moment.” The Germans requisitioned a cart and horse from the villagers, and loaded Jan and half a dozen other prisoners who were in a similarly desperate shape into it. “I had terrible diarrhea and had watery blisters all over my body. I was too weak to relieve myself properly. It was just horrible.”

Suddenly, the Germans disappeared, and that was the end of the war. Jan and three of his friends were in a field, too exhausted to walk to the nearby village. After spending the night in a haystack, one or two managed to go get some help. “The Czech Revolutionary Guards came with a cart and took us to the village, and they put us in one room in somebody’s house with four beds and an empty bucket in the center.” Some people in the village provided food for Jan and his friends. “It was sort of funny because somebody heard we should have light food, so they brought us chicken, and then also butter, and all kinds of things.”

After a few days, they were transported to a nearby hospital. Of the four friends who made it to the hospital, just two survived. “We were together all of the time,” Jan recalls. “We both had frostbite and amputated toes, and later, when we regained enough strength, we were racing around the long hallways of the hospital on our wheelchairs.” The two were released on the same day, but never saw each other again.

THE POST-WAR YEARS

After the war, Jan wrote to a Gentile friend of the family, his father’s secretary, who came to visit him while he was still in the hospital. “Her first words were that my uncle had returned, so I immediately understood that my father, mother, and sister had not. Up until that moment, I did not know, but I suspected.” Jan was devastated. “My girlfriend Eva got my letter and came immediately to visit me and I was delighted that she, too, survived – and was in far better shape than I.” He stayed in the hospital for four months. When he got out, he went to stay with his best friend, Arnošt Reiser, and Arnošt’s sister for a year. “I enjoyed it so much that they, finally, very gently had to remind me it was time to move on.” By then, Jan’s uncle, Otto, was able to get his pre-war apartment back, and he invited Jan to live with him.

Jan hadn’t finished high school, so he enrolled in a special course designed for people who returned from the camps and the army. “It was sort of a fraudulent course where everybody passed and got their diploma within a few months.” Jan then enrolled at the Technical University at the School of Chemistry. He doesn’t remember money being a big concern. Students received fellowships and stipends that were enough to live on, and Jan got some money back that his father had secreted in a bank account.

Three years later, Jan married Eva and moved in with her and her mother. While he and Eva were on their honeymoon in Yugoslavia, news came that the Czech foreign minister, Jan Masaryk, had been summoned to Moscow and ordered to withdraw from the Marshall Plan – a program of reconstruction funds from the United States. Czechoslovakia was now a puppet of Stalin and the Soviet system. “I had an immediate foreboding about what was going to happen,” said Jan. Their relatives suggested the newlyweds go to Germany, where there were camps for refugees. “But the idea of going to a camp in Germany had connotations, so we weren’t about to do that, and then it was too late.”

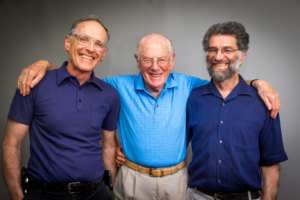

Jan Roček and his sons Tom (left) and Martin (right). (Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch)

Jan was determined to get out of Czechoslovakia after the communists took control. In anticipation of future moves, Jan and Eva gave their children names that were more international, and less Czech: Martin and Thomas. His desire to leave Czechoslovakia, and escape the communist regime, had him coming up with all sorts of plans – from the practical (falsify passports) to the ridiculous (have his relatives in England hire a plane and rescue them by air).

Ultimately, their escape was quite dramatic – he and his family went on holiday by car to East Germany with a group from Prague. On July 24, 1960, they managed to sneak away from the others and board a ferry to Denmark. When the boat reached the harbor at Gedser, Jan, Eva, her 61-year old mother, and their two small boys jumped into the water. It was a very frightening and dramatic moment.

“I lost my direction, I lost my glasses, and I had my four-year-old son with me; I swam on my back with one hand and held him with the other hand.” Eva headed in the opposite direction in the water, with their older son, six-year-old Martin. Jan learned later that a local man on the dock offered to help by taking the boy. “Eva asked him ‘Are you Danish?’ and he said ‘yes’ and she said ‘Are you sure you’re Danish?’ She gave him the boy, and he helped Eva climb up. The Germans had launched a rubber dinghy and were following me.” Another man in the water, presumably Danish, called out to Jan in German to give him the boy. “So I handed him Tom. I already had my hand on the rubber dinghy when one of the Germans said ‘We can’t do anything here.’”

The Danish authorities took Jan and his son Thomas to the railroad station. “There was no communication, so I had no idea if Eva succeeded or not.” After what seemed like an eternity, during which Jan was on the verge of hysteria, a van arrived with Eva, her mother, and their son Martin, and the family was reunited.

Jan Roček and his dog, Jolly. (Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch)

After being rescued, Jan spent a couple of weeks in jail in Denmark, during which time he wrote to some of his colleagues in the west in an attempt to find employment. He was offered a job by a Harvard professor whom he had met at a conference in London. After three months in Denmark, Jan was issued a special visa for scientists, and arrived in the United States to his job at Harvard in 1960. After two years, he moved on to a teaching position at Catholic University in Washington D.C. for four years, and then spent the bulk of his teaching career at University of Illinois in Chicago where Eva was also a professor of chemistry.

In the mid-2000’s, Jan and Eva moved to Wilmington, Delaware, to be closer to their son Thomas, who is an archeologist at the University of Delaware, and his wife, who is a well-known anthropologist. Jan’s older son, Martin, and his wife are science professors at Stony Brook University in New York. Jan has four adult grandchildren. His beloved Eva passed away in 2015.