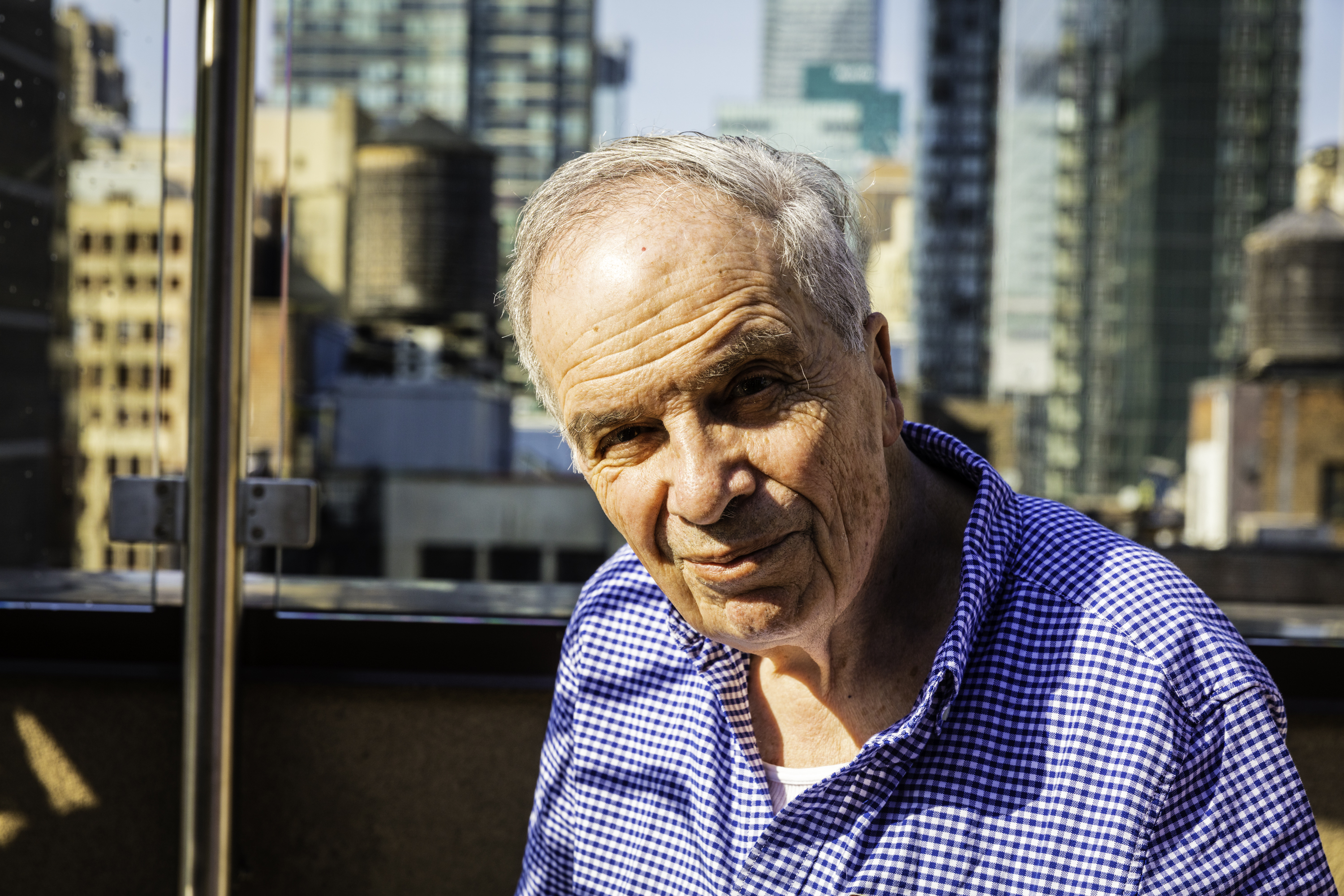

Pedro Seidemann

Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch

Pedro Seidemann

Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch

Pedro Seidemann

A Life Profile

BY GAIL WEIN

Pedro (Petr) Seidemann was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia, in 1931 and has lived in Caracas, Venezuela, since 1948. He spun his meager education into a top executive role at a multi-national corporation, having worked his way up the ladder from an entry-level position as a clerk. He worked for Thyssen, a German company, which he initially hesitated to join after surviving three years in a Nazi Concentration Camp.

Pedro remembers going to grammar school in Prague until Jews were no longer permitted to attend school. When he was 11 years old, he and his mother and father were transported to the Concentration Camp in Terezín. He remembers the exact date: December 18, 1942.

They were permitted to bring a limited amount of luggage, and they, along with the other 1000 people in each transport, were assigned numbers. He remembers his number, too, 593 on Transport CK. The train arrived to a station about 2 km from the camp, and Pedro, his parents and the others on the transport had to walk from there.

Arriving in Terezín

Pedro was sent to a building which had been a high school, with other boys his age, while his parents were assigned barracks elsewhere in the camp. “In one of the rooms, which I remember was No. 9, there was a schoolroom for about 30 boys. We were about 45 to 50 people in that room, sleeping on cots three levels high.”

One of the boys was about five years older than the rest, and he took on a leadership role. For instance, when somebody was away sick, he arranged to distribute that boy’s food ration to the other children. That boy, a friend of Pedro’s named Arno, organized the children into something like clandestine Boy Scouts. Pedro reflects upon that as a positive experience. “That was very good for us, because we had some activity and we were together.”

Pedro Seidemann. Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch

Pedro had a job in Terezín as an assistant to a plumber. He recalls learning how to “work with a chisel and sinks and how to make a hole in a wall to put a pipe through.” Even now, his wife finds this amusing, as Pedro has a reputation in his family for not being ‘good with his hands’.

Pedro, along with another boy named Martin Glas, produced a monthly magazine in the camp. “It was called “Domov,” which means “Home” in Czech. It was handwritten; my mother helped to get us paper from the central office where she worked, elsewhere in the camp.”

It was written by boys, for the boys. The content – five or six pages – included a serial story, with a new episode in each issue. “Nobody knew how it was going to end; even we didn’t know,” said Pedro. It also contained some descriptions of far-away places that the boys collected from their fellow prisoners. One of the other prisoners had been to South America, for instance, and they wrote a travelogue about it for their magazine.

There was, of course, only one copy of each issue. Pedro kept half of them, and Martin the other half. Years later, Pedro donated his magazines to the museum at Terezín. When he finally visited the museum, he realized, ironically, “I paid an entrance fee to see my own work.”

Pedro remembers the day the International Red Cross came to visit the camp. In preparation, the Nazis created a ‘Potemkin Village’. “They painted all the houses on the street that the Red Cross was to drive on, they did all kinds of cleaning and repairing on the street,” said Pedro. “I remember like today when the convoy came, all the cars were white with red crosses, and there were trucks, ambulances and so forth. We were a group of boys, and some of them tossed out some chocolates and candies to us. It was very emotional,” said Pedro. “That was a sign that the outside world knew about us. That was one of the things that buoyed us very much.”

A serious operation

“I was quite a sick boy, so the fact that I am sitting here is really a set of coincidences. I can’t explain it any other way.” Pedro had a number of health issues: he had kidney problems, he may have had Typhoid fever, and he had a problem with the bone behind his ear, for which he underwent a serious operation in the camp. “The medical doctors, who were also prisoners, were first-rate surgeons. We had professionally the best attention you can think of, but they didn’t have much in the way of supplies or facilities,” he said.

“They had to use a chisel to break the bone, and that was the one I was using as an assistant to the plumber. It’s hard to believe they used that. They tried to sterilize it by putting it in boiling water. The doctors told my parents, if we can save his life don’t expect him to ever hear well. And they were wrong; I hear fairly well.”

Post-op recovery was very painful, especially the procedure of changing the dressing. After he recovered from the operation, he fell ill again. “The prescribed diet for this illness was a joke,” said Pedro. “What I was supposed to eat was impossible to get in a Concentration Camp.”

Father's deportation

Pedro’s father was deported to another camp in September 1944. “That was a very traumatic experience for me, saying goodbye to my father,” said Pedro. “We didn’t know that we will never see him again, but there was some kind of a sixth sense. That’s a scene that I will never forget.” A friend who knew both father and son was at Auschwitz and reported seeing Pedro’s father alive as late as January 18, 1945.

Liberation

On May 5, 1945, two days before the war officially ended, the Germans began to leave. Low-flying British aircraft materialized, shooting at a small airport next to the camp that the Germans had set up. “A friend of mine and I, we climbed up on one of these things that goes around, and watched the air fight,” said Pedro. “The Russians came all the way from Berlin to Prague, and that highway went right through the camp. They had everything: tanks, trucks, cars, Jeeps, horses, you name it. It took them about 24 hours to go through.”

“The first thing the Russians did was to declare a quarantine. They said, ‘Now we are liberating you, but nobody leaves, because there are too many sick, too many illnesses.’” Friends from Prague came to Terezín to look for Pedro and his family. “My mother couldn’t leave, but I did. I escaped, to tell you the truth. Our friends said, ‘You know, the Russians are not going to shoot at a young boy,’ so I ran out through the prohibited zone, jumped into the truck and we left. I came to Prague with my possessions, which were short pants, wooden shoes and a little pencil about this tall. That was everything I had.”

About two weeks later, the Russians opened up the camp and Pedro and his friends went back to the camp and found his mother and brought her back to Prague.

Returning home to Prague

“When I arrived in Prague, there was news here and there about people who were confirmed dead, and people who survived the camps but were somewhere else. At the Jewish cemetery in Prague, they posted notices on the doors and walls at the entrance. It was terrible, because you were looking at one list hoping to find your father, then you were looking at a second list hoping to not see his name. We were hoping to find our father and we never did.”

“I was one of the first persons who came from a Concentration Camp back to Prague. Our friends knew of an apartment on the opposite side of the street, which was occupied by Germans who fled at the end of the war.” With his friends’ help, Pedro applied for and was given the apartment. He was 14 years old.

In Prague, Pedro returned to school, to the high school where he belonged according to his age, even though he had not attended classes for five years. He had some basic knowledge of science and mathematics, and became bilingual in English and Spanish. “They allowed me to be a student in my class. In the end, I was among the three or four students who made the highest notes at the end of the school year,” Pedro said proudly.

Coming to Venezuela

In 1948, Pedro’s uncle was finally able to get a visa for Pedro and his mother to join him in Venezuela. The two flew from Prague to Zurich and took a train to Genoa where they boarded an émigré boat bound for South America. “It took us several weeks,” Pedro recalled of the crossing. “It was an old boat, and it was not very comfortable.”

When Pedro arrived in Venezuela, he knew about five words in Spanish. His uncle sent him to a high school, where he was placed in the lowest class. “The first day I came home, I was crying because they were all poking fun at me and I couldn’t speak with them. But then, I remember, they gave an arithmetic exam, which for me was easy, because I was four years older than the rest of the class.” Pedro finished the exam and passed the answers around to his classmates. “I became the most popular guy in the classroom.”

Pedro enrolled in the university in Venezuela, having had less than five years of formal schooling. He studied civil engineering, which also was his father’s profession. After two years of his study there, political problems arose in Venezuela and the university was closed for over two years. “At that time I didn’t feel I should be dependent on my mother, as the sole survivor of our family. So I went to work; I never studied again.”

The beginning of a career

Pedro got a job in an office at a company owned by Czechs. His uncle and his mother had connections in the Czech and Jewish communities, which helped him to acquire this position. He started out as a clerk in the filing department, checking inventory.

It was a steel distribution company, and Pedro found that the work of selling steel domestically came naturally. So he began to try his hand at international business and met with some success. “I got in touch with a German conglomerate called Thyssen,” said Pedro. “After some time, they offered me a job to manage their Caracas office, which was a representative office of their multi-national conglomerate of about 160 companies.”

Pedro Seidemann. Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch

“When they offered me the job I went to consult with my mother, knowing very well of the suffering that she endured at the hands of the Germans. Her answer was immediate, ‘Yes. It’s a challenge, take it.’ It was indeed a challenge, me having survived a German Concentration Camp, working for a German company.”

Over time, Pedro had learned some English. “My father taught me a little bit, a few words. After the war, I maintained my interest in English, because I realized it was an international language. When I came to Venezuela, I had a hobby, amateur radio, which is mostly done in English. So that helped me also.”

Pedro ultimately met his first wife, an American who lived in Florida, through his interest in amateur radio. They met in the early 1960s. Later they divorced and Pedro married a Venezuelan who was educated in Europe and speaks several languages. They met through a group of mutual friends and married in 1978.

Retired, but still working

“I retired from my official job when I was 63, and I never stopped working. The Thyssen company had a corporate policy that at age 65 you were required to retire. I decided to go by myself, before somebody says to me, ‘It’s time for you to go.’” And the first thing they said, “You cannot go. We don’t have any replacement, can you stay six months more?”

That extension was requested several more times. When Pedro finally retired, the president of a Venezuelan group with whom he had done some joint venture work asked Pedro to work with him. “I even traveled to Germany to speak with my prior colleagues, and I managed to maintain good personal relationships with those guys. I am still connected with that Venezuelan group [called Diproinduca], which is incorporated in Canada.”

Personal experience as a history lesson

“The anti-Semitism before the war was easier to understand. It was much worse, but it was easier to understand. After the war, it was more painful, so to say. But now, with 70 years after the war, I am coming to the conclusion that it is not so much the anti-Semitism that should worry us.”

“It’s the way history plays out that people forget. So much time has elapsed that memories fade, political systems change. You take a look at the political situation: friends today, enemies tomorrow and vice versa. So, over the long years, it is a question of forgetfulness, like what my daughter Linda says that people say to her, ‘Was there more than one Concentration Camp? Was there a camp at all?’ But I don’t fault the people who don’t know, because of the incredibly long elapsed time.”

“Still today, I have to remind myself that my personal experience is history to other people. I am very honored and pleased that I can give my grain of support to The Defiant Requiem Foundation, because it is doing a wonderful job so that the forgetfulness is reduced, and that is an important mission.”

For more photos of Pedro, please visit our photo gallery.