Edgar Krasa

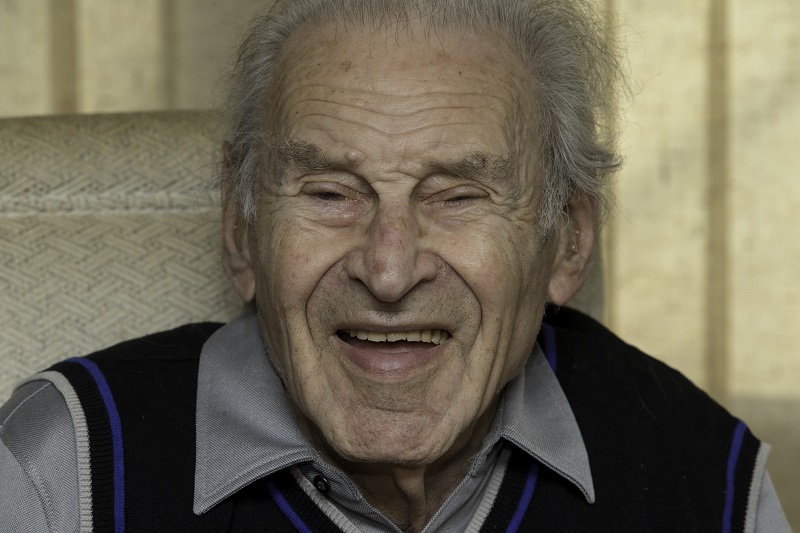

(1924-2017)

Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch

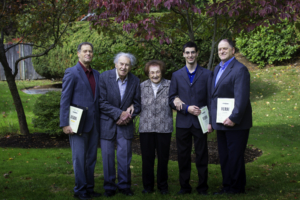

Edgar and Hana Krasa.

Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch

Edgar and Hana Krasa.

A Life Profile

BY GAIL WEIN

Edgar Krasa’s decision to become a cook saved his life more than once, saved his parents’ lives, and took him from Prague to Israel, Tasmania, New York and ultimately to Newton Centre, just outside of Boston, where he lived since 1963.

Edgar Krasa stands in the kitchen where he worked as an apprentice. Photo credit: Jacob’s Relief

Edgar Krasa was born in 1924 in Karlsbad, in the German part of Czechoslovakia, Sudentenland. In 1933, with pre-war pressures already mounting, the family moved to Prague. When Edgar was around 14, his aunt encouraged him to learn to cook, so that he would always be around food. He became a cook’s apprentice, and began working at the restaurant where he trained. When the restaurant he worked at was no longer permitted to employ Jews, he went to work for the Jewish Community Center, cooking for the new influx of Jewish refugees from Poland and Austria.

In 1941 the manager at the Prague dining hall where he worked was charged with setting up the food service at Terezín, about 60 km away. Krasa was asked to ‘volunteer’ to set up the kitchens in the new Jewish ghetto, and in exchange, his parents would be protected from deportation further east. The manager kept his word. Though his parents, Louis and Elsa, were sent to the Terezín Ghetto, they survived, and were reunited with Edgar after liberation.

To Terezín

On November 24, 1941, Edgar Krasa travelled from Prague with more than 300 others – engineers, technicians, draftsmen and other professionals, to convert the town of Terezín into a concentrated ghetto for the Jews. When this “Construction Commando” arrived, there were no beds, so the men slept on straw on concrete floors until carpenters built triple bunks in the barracks. Beginning a week later, transports of a thousand people at a time began to arrive at Terezín, including Edgar’s parents, who arrived on December 14, 1941.

Rafael Schächter, a pianist and conductor, was on one of those early transports from Prague. Right away, Rafael Schächter invited inmates to gather every evening to sing Czech patriotic songs. Most of the inmates took part. “It immediately changed the atmosphere and mood of the participants,” said Edgar. “The singing brought us closer together, to get to know each other, bonding us”. As Rafael Schächter lifted up inmates’ spirits with song, Edgar Krasa wanted to do the same for their stomachs. As a cook at Terezín, he created some familiar Czech dishes, making do with his meager supply of ingredients.

By the following summer, in July 1942, the original, non-Jewish residents of Terezín had left, or were relocated, leaving the homes around the village vacant. At that point, some of the inmates moved from the crowded barracks to these houses, and this is where Edgar Krasa shared a small attic room with Rafael Schächter.

Some of the deported Jewish music lovers, both amateurs and professionals, ignored the official order to turn in their musical instruments, and smuggled these into the Ghetto as part of their 50 kg allotment of luggage. At some point, the Germans found out about these contraband instruments, and it was feared that a punishment would be levied. However, the head of the Jewish Council of Elders attempted to salvage the situation. He suggested to the Commandant that he take advantage of all the talent in the Ghetto, and use it to show the world how well they are treating Jews.

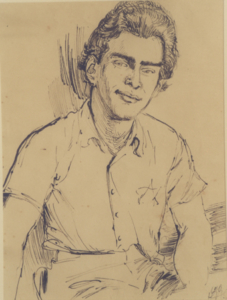

A 1943 portrait of Edgar Krasa drawn by Leo Haas in Theresienstadt. Photo credit: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Edgar and Hana Krasa

Astonishingly, the Germans “fell for it” and brought in even more instruments from a warehouse in Prague. A “free time activities department” was created, and a choir was organized which Rafael Schächter led and in which Edgar Krasa sang. “These performances allowed the performers and the audiences to immerse themselves into the world of art and happiness, forget the reality of Ghetto life and deportations, and gather strength to better cope with the loss of freedom,” said Edgar Krasa.

The composers, performing musicians and artists all had other jobs in the camp, and they worked their craft at night. Recognizing that these people were shouldering double shifts, Edgar found ways to get them additional food, and became very friendly with them.

Rafael Schächter decided to take on the challenge of learning and performing the Verdi Requiem. Edgar sang in all 16 of the performances, including the final performance, which was at the request of the Nazis. This was to be for the delegation from the International Red Cross, who were visiting Terezín to inspect the conditions of the camp, accompanied by the camp commander and high-level SS officers. “We were all happy to have told the Germans what is awaiting them,” said Edgar, referring to the Requiem’s message that all will be judged by God upon their death.

After the Red Cross visit, the Germans – in order to prevent any possibility of an uprising (which had recently occurred in the Warsaw Ghetto) – deported every able-bodied person from Terezín. Nineteen thousand people, including Edgar Krasa and the Council of Elders, were deported within one month in the fall of 1944.

Deportation To Auschwitz

Edgar Krasa left Terezín on a train headed for Auschwitz, every car jam-packed with prisoners. There was not enough space for all to sit, and the inmates were not provided any food or drink during the airless, hot, cramped and nearly unbearable three-day journey. During this journey, Edgar befriended Jirka Brady and Leo Kohn, both 15 years old. His paternal instinct kicked in, and Edgar made it his mission to stay near these younger boys and take care of them through their time at Auschwitz and beyond to the end of the war.

On the train platform at Auschwitz, two white-gloved SS officers assessed each prisoner. Anyone capable of working, including Edgar and the two boys, went to one side; and everyone else, including mothers with children, boys deemed to be too young to work, and old, sick or disabled people, were directed to the other side and were murdered in the gas chambers that same day.

“While moving ahead I saw a chimney spewing not only smoke, but also sparks and flames. Naively, I asked the guard accompanying us why the flames. He responded that this is the bakery, and they must have burned a whole load of bread. Of course even this secret was revealed later,” said Edgar.

After discovering the real purpose of the five chimneys at Auschwitz, Edgar and the other prisoners were desperate to get away. Civilians accompanied by officers were often coming to the barracks to look for workers for nearby factories. If they were looking for bricklayers, all the Jews were suddenly bricklayers. In the case of Edgar and his two young associates, they claimed to be welders and were subsequently sent to work in a railroad yard.

“As a ‘good-bye present’, the Nazis tattooed a number on each of us, which became our sole identification,” said Edgar. “Three prisoners were doing the tattooing and I went to look at each one to see which did it the nicest. I still cannot understand why it was important to me that my number was neat,” he said. Years later, the tattoo sparked curiosity in his son Daniel Krasa (Dani) when he was a youngster. “I asked him what was the number on his arm; he said ‘it’s our telephone number.’,” Dani recalls. “I said, ‘We don’t have a telephone.’ And he said, ‘Well, that’s what it will be when we have one’.”

The Welder At Gleiwitz

Edgar and the other prisoner-welders were transported by train in cattle wagons, traveling several hours to the city of Gleiwitz. There were around 3,500 prisoners working at the railroad repair shop. Edgar and the others worked 12 hours a day, six days a week. On Sundays, the shop was closed, however work never stopped for the laborers; they were required to perform menial tasks like moving boulders from one end of a quarry and back again.

Each inmate received a blanket for their wooden bunk. They were not issued pillows, so they used their shoes as a pillow, the additional advantage being that the footwear was less likely to be stolen that way. Edgar Krasa had wooden Dutch clogs, which provided good insulation from the snow, but they were uncomfortable to both wear and sleep on because of their inflexibility.

Though Edgar and his fellow prisoners were out of Auschwitz, his life as a laborer was not easy. Roused at 4:30 am to be at their posts by 6:00 am; twelve-hour shifts fueled by a slice of bread in the morning and thin soup at noon. One visit to the bathroom per workday was permitted, and the men’s tattooed numbers were checked to prevent any abuse of this policy.

The Death March

On January 19, 1945, guards gathered the prisoners and evacuated the camp. Edgar and his two younger cohorts managed to stay together, and they, along with the rest of the inmates, were marched out of the camp. “It was not a march with everybody in step,” Edgar recalled, “each walked as best as he could, because we were constantly pushed to hurry. After some time, people were slowing down, but could not stay behind. All those who could not keep up were shot on the road.” The Death March had begun.

Late that night, the prisoners arrived to a camp that had already been vacated. There they had a few short hours of sleep, before being awakened before dawn, and prodded on their way on foot once again. During all of this time, the prisoners had no food or drink, only dirty snow picked up from the road.

On the afternoon of the second day of the Death March, Edgar’s wooden shoe broke. He wrapped his feet in scraps of wax cloth and he had no choice but to continue. Again, the prisoners had no break or rest, marching till late into the evening, and getting a few hours of sleep in a barn.

The Escape

Now the prisoners were on their third day of marching, from dawn into the evening, once again with no food. Edgar, feeling weaker and weaker, realized he had to make a choice. If he were to simply stop marching and fall on the road, it was certain that a guard would shoot him. “If I try to escape I might get shot too,” Edgar reasoned, “so the result would be the same.”

That night as they passed an area with woods on both sides of the road, he decided to chance it. Edgar dropped into a ditch by the side of the road, and laid motionless. As expected, one of the guards shot him in the torso to make sure he was dead. Bleeding into the snow and emaciated from three years of malnutrition and overwork, Edgar weighed only about 70 pounds by then.

Edgar Krasa (Photo credit: Michael Lutch)

The troop made its way down the road without Edgar. After all the marchers had passed, he ran into the woods and found a few other escapees. One of them was able to pry out the bullet which had lodged in Edgar’s rib. After a few hours sleep, outside in the dark and cold, this small band ventured back out to the road and spotted a prisoner camp on the top of a hill. But its gate was open, the watchtower was empty, and the prisoners were wandering freely. Edgar and his group made their way to this camp, Blechhammer, where they learned that before dawn, the guards had jumped into their trucks and left in a huge hurry. They were liberated, but the place was chaos with hordes of desperate people. They had no water, they had no electricity.

Edgar and his fellow ex-prisoners scoured the nearby village, which had also been hastily abandoned by its residents, and scrounged up food and other supplies from the surrounding homes. “I found a gallon jug with roasted pork, filled with lard,” recalls Edgar. Famished to the point of starvation from the poor nutrition at Gleiwitz and from three days without food during the march, “I put my hand into the jar, and ate a fistful of the fat. All of us ate without self-control and sense.”

They stayed at Blechhammer for six weeks. “We were too weak to get all the way home on our own, and besides, the war was still going on between Blechhammer and our home,” said Edgar. With food provisions gathered from the village and augmented by some livestock from a nearby pig farm, Edgar and the others replenished their starving bodies. In those six weeks, Edgar gained nearly 80 pounds.

Coming Home

The group made its way to the nearest large city, Katowice, where Edgar quickly got a job as a cook in a cafeteria for factory workers. By the middle of April, Edgar and some of his companions started for home, needing to take a roundabout route in order to avoid Slovakia, which the Germans still held at that point. They were in Budapest on May 8, 1945 when the end of the war was announced, and there was dancing in the streets and loud celebrations.

Once he reached his hometown of Prague, Edgar went straight back to Terezín to find his parents. Although the camp at Terezín was liberated, the Russian army had put it under quarantine to in order to prevent the spread of typhus, scarlet fever and other infectious illnesses. No one was allowed in or out. Edgar Krasa convinced a guard that he himself had typhus, and so was able to enter the camp, and had a very emotional reunion with his mother and father.

After securing a furnished apartment, Edgar brought his parents home to Prague. He got a job at the same restaurant where he had apprenticed. The family needed money for food and clothing, and so Edgar took on a second job in the evenings at a restaurant-bar.

Hana Krasa. Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch

In October 1946, Edgar’s civilian life was put on hold when he was drafted into the Czech military reserve. He was slated to serve five months in northern Bohemia. However, when the United Nations asked its member countries to reduce their forces, Edgar was discharged early, on December 31, 1946.

It was December 31, and Edgar had just gotten out of the army. So he went to a New Year’s Eve party to celebrate. This is how Edgar Krasa met Hana (Hanka) Fuchsova, whom he married in 1949. Although Edgar and Hana were both at Terezín, they had not met until this party.

Switzerland

In 1947, the economy was still poor in Czechoslovakia, and Edgar was resourceful. He wrote to the Chamber of Commerce in Bern, Switzerland, and the Chamber arranged a summer job for Edgar in Interlaken. This led to another job in Lucerne, then another in the ski resort town of Arosa, and finally one in Lausanne.

The government in Czechoslovakia – now run by communists – didn’t extend his exit visa, and Edgar’s father insisted he return to home to Prague in the summer of 1948. The State of Israel had just been created, and Edgar was determined to settle there.

He figured he would stay with his parents in Prague, only as long as the borders remained open to emigration. He took a job as the chef at the Israeli Embassy in Prague, and reunited with Hana. They married at the end of 1949. Within a year, the borders closed without warning, a sudden end to legal emigration. Hana was expecting, and the couple was determined to leave the country, legally or otherwise.

Emigration

In order to get out of Czechoslovakia, Edgar and Hana arranged for false passports with different identities but their own photos. They were able to sneak onto a train headed for Venice, where they planned to get on an Israeli ship to Haifa. But there was a snag. At the border crossing in Italy, the authorities took a close look at Hana’s papers which had a man’s name, not a woman’s name, on them. The couple was pulled off the train and sent to jail in Austria.

Within a couple of days, a British officer questioned them, took them out of the jail and brought them to a displaced persons camp. After several weeks, Edgar and Hana wound up in jail again, this time in Salzburg. They had attempted to get on a transport to Israel there, but that transport never materialized.

Men and women were held separately at this jail, and so Edgar and Hana were in different cells. Hana was in a jail cell with some prostitutes, but she herself was quite naive. When she finally saw Edgar, the first thing she said was “Eda, what is gonorrhea?”

Israel

Finally Edgar Krasa was able to contact the Israeli embassy in Vienna. They were taken to Venice, where they were able to board a ship to Israel. Edgar found work at a hotel near Tel Aviv, and Hana got a job as a seamstress. Before long, Edgar secured a better-paying position as a chef in Haifa, and the same week he began this position, Hana gave birth to their first child, Dani.

Life was still not so easy in Israel. The country had a large population, food staples such as meat were tightly rationed, and wages were low. Nonetheless, Edgar fared well, working and providing for his family, which grew with the birth of the couple’s second son, Rafi (Raphael), named for Rafael Schächter.

United States

Edgar wanted to see how life was in other places. So, he got a job as a chef on a cruise ship, the first passenger line that was headed to the United States. He had two cousins in New York, and one of them offered to give him an affidavit in order to immigrate there. Since Edgar had no official documents – all of his papers had been lost or burned by the Nazis in the war – it took many years to get processed. In the meantime, Hana gave birth to the couple’s second son, Rafi (Raphael), named for Rafael Schächter.

Edgar and Hana Krasa with their family. Photo credit: Michael J. Lutch

Terezín Chorus Survivor Edgar Krasa is lifted into the air by his son Rafael – named for Rafael Schächter – as older brother Daniel (Dani) looks on in a scene from the award-winning documentary, Defiant Requiem. Photo credit: Partisan Pictures

The United States was not Edgar’s only overseas travel. When the country of Tanzania gained independence in 1961, the Israeli government sent assistance in the form of technical and professional training. Edgar was sent there to help train the locals in hotel service to accommodate the anticipated surge in tourism.

He also set up the first culinary school in Israel, in a hotel that the government had taken over. The school is still in operation, and its admission is very competitive.

Finally, in 1962 Edgar’s papers came through, and the family was able to emigrate to the United States. They started out in New York, where Edgar found work as a night manager in a restaurant. The following year he secured a job in Boston as food service director at a large institution, the Hebrew Rehabilitation Center. The center was so new, it wasn’t even built yet. Edgar worked there for many years, until his retirement. Over the years, Edgar has spoken to thousands of students across New England, dedicating his life to educating young people about the horrors of the Holocaust.

For more photos of Edgar, please visit our photo gallery.