A Tribute To Amy Antonelli: A Musical Life: 1941-2014

Amy Solit Antonelli lived a rich life centered on family and music. She was a pianist, teacher, college professor and assistant dean, and a leader in Washington choral music. She was a devoted wife and mother and the beloved friend of everyone who knew her.

Amy Solit Antonelli lived a rich life centered on family and music. She was a pianist, teacher, college professor and assistant dean, and a leader in Washington choral music. She was a devoted wife and mother and the beloved friend of everyone who knew her.

Born on April 23, 1941 in Brooklyn, N.Y., Amy Rachel Solit was reared in the Flatbrush neighborhood, in a family with innate musical talent, if not formal music education. Her paternal grandfather had been a cantor in Russia. Her father, Maurice Solit — a history teacher and later school principal — played the piano by ear. Her mother, Freda, of Ukrainian descent, had a lovely singing voice.

Amy’s musical studies began when she was eight, on a piano given to her family by an aunt. Her first piano teacher, sensing that Amy had a special gift, passed her along to Rose Cion, a noted New York teacher and piano recitalist, who taught Amy for a decade.

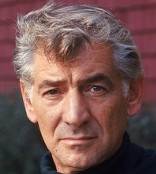

When Amy was a young teenager, she first experienced the prodigious talent of an exuberant conductor and pianist who, in live televised concerts beginning in 1954, introduced millions of young Americans to the joys of orchestra music. His name was Leonard Bernstein, and for 18 years his lectures and concerts on CBS became must-see TV in homes all over the world.

Amy Solit was captivated by the charismatic young conductor of the New York Philharmonic, and she soon sent him a fan letter. When Bernstein’s younger sister, Shirley, was working on a book about her brother in the early 1960s, she came across Amy’s youthful fan letter in the maestro’s files and got Amy’s permission to quote it.

Amy Solit was captivated by the charismatic young conductor of the New York Philharmonic, and she soon sent him a fan letter. When Bernstein’s younger sister, Shirley, was working on a book about her brother in the early 1960s, she came across Amy’s youthful fan letter in the maestro’s files and got Amy’s permission to quote it.

Amy Antonelli’s association with Robert Shafer, and in turn The City Choir of Washington, began when she served on the search committee that brought him to the Oratorio Society. Bob’s first year with the Oratorio Society, 1971, was also the year that Amy became its board president (a position she held for 18 years) and de facto executive director — scheduling concerts, hiring soloists and venues, managing publicity, and doing it all as an unpaid volunteer in the days before professional arts management came to small organizations.

1971 was also the year that Amy assumed the important position of rehearsal accompanist, a role she fulfilled for the next 42 years, with the Oratorio Society/Washington Chorus and later with the City Choir of Washington. Under Shafer’s musical direction and Amy’s administrative leadership, the Oratorio Society grew in stature and fame through its own concert productions and in guest appearances in Washington, New York and overseas.

In 1971, former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy commissioned Leonard Bernstein to compose a theatrical work for chorus, soloists and dancers — entitled Mass — for the opening of the Kennedy Center. Norman Scribner (who founded the Choral Arts Society in 1965) was asked to provide a small chorus of 60 voices for the new work. Amy was one of 500 singers who auditioned for the pick-up chorus (dubbed “The Norman Scribner Choir” for the occasion), and she was accepted into the alto section. Amy had never met Maestro Bernstein, the idol of her childhood years in New York City. But at the first rehearsal for Mass, Amy walked right up to him and introduced herself as that long-ago teenager from Brooklyn who had sent him a fan letter.

In his inimitable way, Lenny embraced Amy — literally and figuratively — and from then on, she was his informal liaison to the Mass choristers and a dear friend forever. After bonding with Lenny during Mass, Amy asked him to be a member of the Oratorio Society’s honorary board. He readily accepted.

In the three decades since its Kennedy Center debut in 1972, the Oratorio Society/Washington Chorus made more appearances with the NSO than any other chorus — in fact, more than any other NSO guest artists. At rehearsals for the concerts, Amy served as accompanist under such renowned conductors as Seiji Ozawa, Sir Neville Marriner, Margaret Hillis, Mstislav Rostropovich, Sarah Caldwell and Leonard Slatkin.

In January of 1973, Leonard Bernstein — a passionate champion of liberal causes his whole life — came to the capital to conduct an anti-war concert at the Washington National Cathedral. Billed as a protest of President Richard Nixon’s election to a second term, the “counter-inaugural” concert featured Haydn’s Mass in Time of War, with singers pulled together from several choral societies in D.C. At the first rehearsal, Bernstein looked about for Amy, whom he had assumed would be providing the accompaniment. But their mutual friend Norman Scriber told him that Amy had a prior commitment with her own chorus, the Oratorio Society, and couldn’t be there. The famous maestro asked for her phone number, and — in the throes of preparing for his own big production — called Amy to wish her good luck with hers.

It would be 13 years before their artistic paths would cross again. Bernstein was active in a group of artists called Musicians Against Nuclear Arms, and he came to the capital in January 1984 to conduct Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 (the “Resurrection Symphony”) at Washington National Cathedral with musicians from the NSO and Baltimore Symphony, and a pick-up chorus recruited by Scribner and Shafer.

Amy joined the chorus for the performance, and she also provided piano accompaniment for the soloists’ rehearsal in a small room at the cathedral. There she was at the keyboard — while Bernstein worked with two of the greatest operatic voices of the 20th century, mezzo Jessye Norman and soprano Barbara Hendricks — when a camera crew showed up to film the rehearsal for the CBS Sunday News with Charles Kuralt. Footage of Amy accompanying Jessye Norman was aired that week on the popular Sunday morning program, and it was also used later in a TV special on the great African-American diva.

During a break in that session, the cameras were still rolling when Amy introduced her daughter, Erica, to the great maestro. Amy was captured on camera exclaiming to Lenny, “You’re such a nice man!” exhibiting the guileless joy that was Amy’s trademark. This footage of Amy’s simple, heartfelt compliment to the great maestro was later used by CBS News in its tribute to Bernstein when he died in 1990.

Another of the great conductors who became fond of Amy was the irrepressible Mstislav “Slava” Rostropovich — the brilliant cellist, former Soviet dissident, and music director of the NSO from 1977 to 1994. The Oratorio Society/Washington Chorus performed many times under Slava’s baton, and Amy accompanied every chorus rehearsal for those works. Each time they met, Slava enveloped her in his Russian bear hug with kisses on both cheeks.

At a full orchestra and chorus rehearsal of Randall Thompson’s Testament of Freedom on the National Mall, below the U.S. Capitol steps (part of a July 4th NSO performance), Slava stopped and called out, “Amy, you conduct — I want to hear how it sounds out there!” With nowhere to hide, Amy dutifully did what the maestro ordered: She mounted the podium and conducted, while Rostropovich roamed the grounds, listening to the sound. Then Slava shouted, “Play it again!” — which they all did, still under Amy’s direction.

After an evening rehearsal with the NSO and Oratorio Society for a particularly difficult work (by the contemporary composer Jacob Druckman), Slava invited Bob Shafer, Amy and Amy’s husband, Morris, back to his apartment near the Kennedy Center, and over a bottle of vodka, he told them stories of his Russian friends Shostakovich (one of his conservatory teachers) and Prokofiev (who wrote a cello sonata for him).

Amy’s work with the distinguished conductor Murry Sidlin on Defiant Requiem: Verdi at Terezín, a concert-drama featuring the Verdi Requiem, along with an associated documentary film, and the formation of The Defiant Requiem Foundation — were among the most satisfying professional experiences of her later years.

Amy met Murry Sidlin in the early 1970s, when he served as resident conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra under music director Antal Dorati and Amy’s Oratorio Society was beginning to do frequent guest appearances in NSO choral productions. They kept in touch over the years as Sidlin’s career took him to music directorships at symphonies in New Hampshire, Long Beach, Tulsa and Oregon, guest conducting all over the world, and more than 33 summers of teaching conducting at the Aspen Music Festival.

When Sidlin returned to Washington to be dean of the Benjamin T. Rome School of Music at The Catholic University of America (2002-2010), he and Amy became professional colleagues. In addition to her impressive musical activities in the capital region, Amy forged a formidable academic career, earning a Ph.D. from Catholic and serving as assistant dean for admissions and undergraduate and an adjunct professor of theory in the School of Music.

While doing academic research on music composed and performed by Jews during the Holocaust, Sidlin came across the incredible story of multiple performances of the Verdi Requiem by Jewish musicians at the Terezin concentration camp in Czechoslovakia, under Czech conductor Rafael Schächter, who was later killed on a death march after imprisonment at Auschwitz and other death camps.

Sidlin set out to discover why and how those Jews decided to learn and perform this dramatic musical setting of the Catholic Requiem Mass (in Latin), and how — in some mysterious way — it represented their personal defiance of Nazi authority.

Sidlin’s global quest to find Terezín survivors and hear their stories produced an enduring legacy: a definitive historical account of Schächter’s obsessive and uplifting project; numerous concerts recreating the Terezín Verdi performances; a documentary film; and an ongoing education program to teach young people about human rights, the Holocaust and new paths to a better world.

When Murry formed The Defiant Requiem Foundation in 2008, he tapped his friend and colleague, Amy Antonelli, to be associate artistic director and secretary of the board of directors, posts she held with commitment and pride. Amy also played piano in a special arrangement of excerpts of the Requiem that Sidlin created to be part of the soundtrack for the documentary. Her involvement in the project proved to be a fitting bookend to her own remarkable life of service to music, education and cooperation among peoples.

Murry Sidlin, Amy’s colleague and friend eulogized:

“She believed in what music can provide: hope, courage, dignity, all emanating from its wisdom and beauty. Her first passion was City Choir, and her absolute assurance of Bob’s integrity, his musical power and poetic depth. Then, as an add-on, came the Defiant Requiem, its commitment to the legacy of Terezín through its educational ventures, and on-stage re-telling of the Verdi Requiem saga. Suddenly, her hands and life were completely full, happily so. Each of us still awaits her call, her spin into the room, and the sunshine of her presence. The loss of Amy is profound, actually heartbreaking. Whatever we do as musicians, it must be at the level that would have pleased her.”

In 2007, Robert Shafer and a group of his former singers from The Washington Chorus formed a new choral society, The City Choir of Washington. Amy accepted their invitation to serve as rehearsal accompanist, which she did until illness began to interfere with her professional life.

At the City Choir’s Christmas concert in December 2013, Bob Shafer — Amy’s dear friend and colleague for more than 40 years — led his chorus in the premiere of a new work he composed in her honor, A Spotless Rose. Amy was in the audience to hear the new work and Bob’s moving tribute to her career and their friendship. After leading The City Choir of Washington and members of The Washington Chorus in a performance of the final movement of Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms at Amy’s funeral service, Bob Shafer reflected, “Choral ensembles are quite different from other musical groups. Perhaps it is because singing is such a direct and personal way of expressing one’s self. Amy and I worked closely together for 43 years, and she was one of my closest friends. The loss that I feel is quite profound and devastating right now, and we will be together spiritually forever.”

While leaving a rich professional legacy, Amy’s greatest legacy is the family that she and her husband of 52 years, Morris Antonelli, nurtured with a lifetime of love: their son, David, and his wife, Ari, of Chevy Chase, and their daughters Gabrielle and Margot; their daughter, Erica Antonelli, and her husband, John Charles, of Chevy Chase, and their son Evan and daughter Raemi. Amy is also survived by her brother, Jim Solit, and his wife, Karen, of Washington, D.C.

Adapted from Amy Solit Antonelli, A Musical Life (1941-2014), based on reminiscences of Amy and Morris Antonelli as told to their friend Knight Kiplinger, December 17, 2013, with permission of the Antonelli family. Additional quotes provided by Robert Shafer and Murry Sidlin.

This article was reprinted with the permission of The City Choir of Washington and Knight Kiplinger.