Fred Terna

(1923-2022)

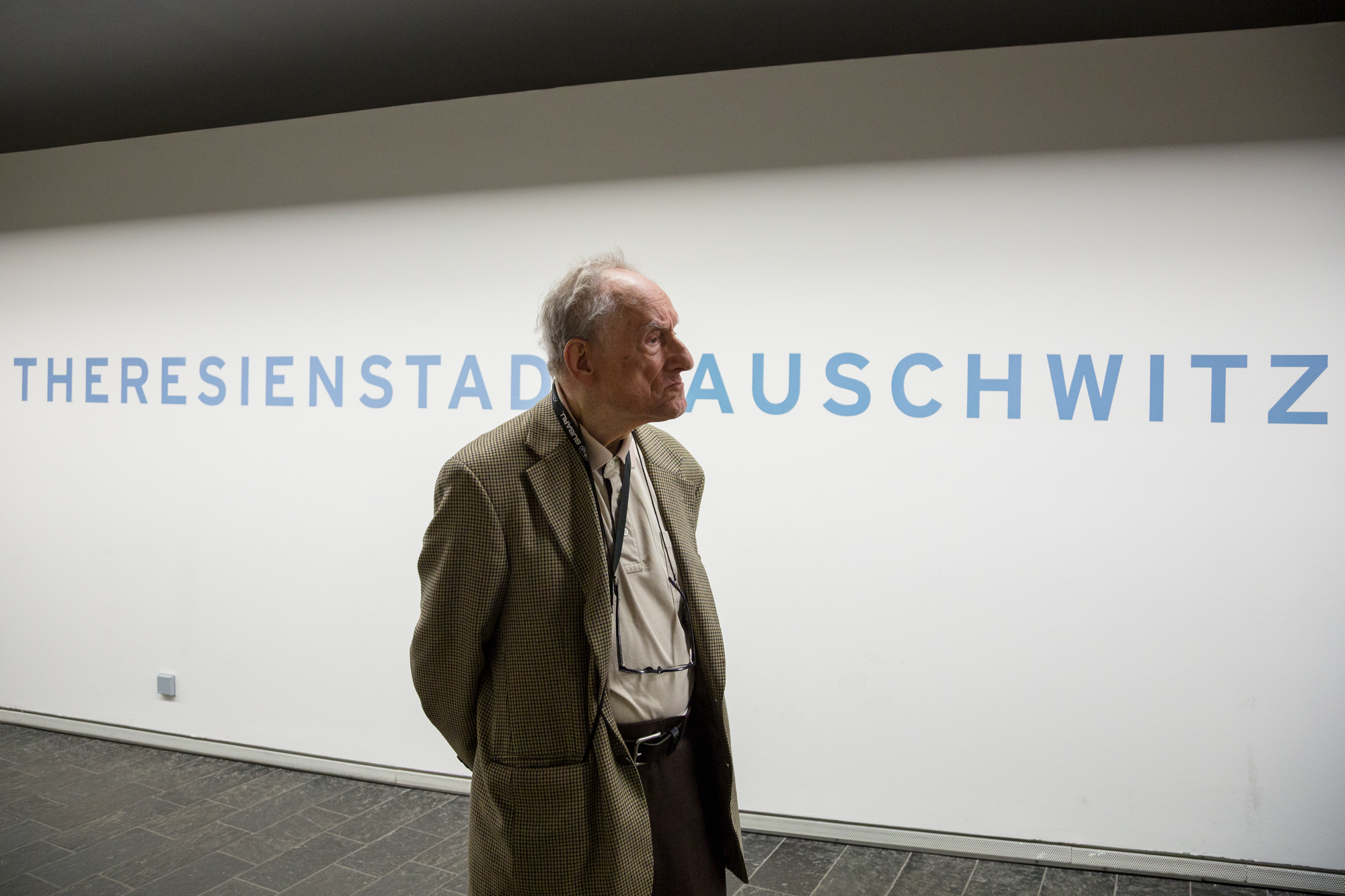

Fred Terna (photo credit: Daniel Terna)

Fred Terna (photo credit: Daniel Terna)

A Life Profile

BY GAIL WEIN

Fred Terna has the energy of a man half his age. He is an active and successful artist, living and working in his Brooklyn brownstone. A gallery space run by his son Daniel is on the lower level of his elegant and spacious home that he shares with his wife, Rebecca Shiffman. His work is included in a number of significant collections around the world, including the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, the Albertina Collection in Vienna, and Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.

Fred was born in 1923 into what he describes as a “typical Prague family” – educated, middle class, Jewish people. His father had a doctorate from the University of Prague and his mother was from Vienna.

Childhood in Prague

The family lived in Vienna and moved to Prague when Fred was two or three, right around the time that his brother Tommy was born. Fred’s father was in the insurance business, specifically marine re-insurance. “We were far from wealthy, but we were comfortable,” Fred said. “I went to school in Prague and these public schools were very, very good, with many Jewish teachers.” In general, these teachers were overqualified; they would have been teaching in universities were it not for anti-Semitism in the pre-1918 Austro-Hungarian Empire. “They were brilliant people, some of them, and so I received a good elementary education.”

Fred’s mother died of pneumonia in 1932, when he was nine years old, and his father never remarried. The extended family lived very close together, “practically within shouting distance, in a very very nice Prague neighborhood, near the museum and St. Wenceslas Square.” At school in Prague, about one fourth of Fred’s class was Jewish, and he was good friends with some of them. There were organized sports, including a Jewish sports club, Maccabi, though Fred did not participate. Instead, his after-school activities included theatre and music.

“My grandparents had a huge bookcase with music. They had two pianos in one big room of their house, and I learned all the early operas from piano extracts, with people singing them around the piano. After age 13 I was allowed to go to the opera.” Wednesdays were music nights at his grandparents’ house. “People would come with their instruments, sit around and have hot chocolate and cake, and make music,” Fred recalled. He remembers those evenings with much joy.

Political Changes/Nazi Occupation

On March 15, 1939, the Nazis marched into Prague. “At that moment, all of the laws of Nazi Germany applied to the Jews of Bohemia. I was kicked out of school, my father lost his business, and my formal education ended at age 15.” Though the family tried to leave the country, it was nearly impossible. To do so, both an exit permit and a specific destination were required.

On the Farm

Fred’s father had arranged for him to be in hiding. From 1939 to 1941, he lived, with false papers, on a farm outside of Prague. It was a large farm on a huge estate. Fred became the owner’s assistant and part of his job was to drive him around the area. When cars were no longer allowed for private use, Fred served as a bicycle messenger. “I learned a lot at that time about agriculture, wheat, and weeds and other agricultural terms.”

Then, in early fall 1941, Fred’s father learned that the authorities were looking for him. “My father sent a message, ‘Home, now! Instantly! Don’t wait a minute!’. So I hopped on the bicycle and bicycled all the way back to Prague.” That evening, the Gestapo arrived at the door of Fred’s home and demanded to see his papers. “I had been betrayed by the game warden, who had betrayed other people, too. In fact, that game warden was shot right after the war.”

Within weeks, Fred was sent to his first camp, Lipa (Linden bei Deutsch-Brod), arriving on October 5, 1941. Lipa was a labor camp – primarily agricultural forest roadwork – run by the Gestapo of Prague. “What was initially a ‘good’ camp, as time went on, deteriorated. It was a ‘good camp’ in that nobody got killed there,” Fred recalled. In March of 1943, all of the people at the camp, about 300 men, were sent to Terezín.

Terezín

Fred was 20 years old when he arrived in Terezín. “I was in the ‘hundertschaft’, the ‘Group of 100.’ We didn’t have a fixed place of work, but we were assigned to whatever work was needed: fixing the roof, digging a ditch, plumbing, painting, this and that. That gave us a certain amount of flexibility.”

“We had a special permit that was supposed to go for a specific job to be out after 8 pm. And of course we abused it coming and going. I used it all the time to attend lectures, to go wherever I wanted, with some common sense. I always had a hammer with me and screwdrivers.”

A music-lover then as now, Fred attended several of the performances of the Verdi Requiem led by Rafael Schächter. “I liked it. I made sure I was in the group that was cleaning up afterwards, particularly the big one, where the SS was in attendance. I liked music and I liked the guys who were singing. I knew some of them, and that was my connection to the Requiem.”

Fred's Father

Fred’s father was in his late 40’s when he was sent to Terezín from Prague. Because of his age, when they shipped people out from Terezín to work, he was sent to Kladno, which was a coal-mining town. “Now you have to visualize a bespectacled professorial-looking Prague Jew suddenly working a coal mine. His work was above ground, but because of lack of food and other things, he contracted Tuberculosis and he was shipped back to Terezín.”

In Terezín, Fred’s father was in a room with other TB inmates; ten of them in a small room in narrow bunks, with straw mattress underneath. “He had the influence to pick people who would be in the room with him, and he chose all high-powered intellectuals. There was a fine collection of brilliant people, all TB patients. I snuck in there as much as I could and that is where part of my political education actually came from.”

“It was a high-powered symposium discussing history, philosophy, you name it. My father was the ruler of the roost of that group. I remember that group with a lot of love and admiration. My father was eventually, like everybody else, shipped to Auschwitz. Soon after, I had been shipped there.”

Auschwitz and Kaufering

Fred was sent to Auschwitz in the fall of 1944. Except for a handful of people, most of the prisoners in his transport were sent immediately to the gas chambers. The transport that Fred’s father was on was no different. But his father was not so fortunate. “Upon arrival in Auschwitz, that transport of his, anybody who was infirm, sickly, went immediately into the gas,” said Fred. “As did my brother in Treblinka in 1942. He was in a transport where there were no survivors at all.”

Upon arrival to Auschwitz, Fred was identified as able-bodied. He and the others in the group that survived the selection were sent to the gypsy camp at Auschwitz, the Zigeunerlager. Around the end of 1944, Fred and some of his fellow prisoners were shipped farther out, to Kaufering, a sub-camp of Dachau. It was construction work, Fred explained. “Nazis were building an underground factory to build the new early jet planes. Essentially it was slave labor that built these things.” Fred recalled, “It was a bad winter. I have frost bites that are still not quite healed…that was a bad, bad place. A lot more people died in front of me there than anywhere else.”

Escape

Fred’s sleeping quarters at Kaufering was in an earthen hut, bunking with his friend Tommy Mandl. He and Tommy were inmates in Terezín at about the same time, though they had not met until they were on the transport to Auschwitz.

Fred related the details of their escape from Kaufering on his website:

Starting in March 1945, at night we could hear the rumbling of artillery further north, and we knew that the Americans were but miles away. While we were still under SS guard the supply system was breaking down. Most of us inmates had been without food for a number of days. In the earth hut where we were housed some were dead, probably from starvation, disease or exhaustion. Suddenly, in the middle of a night we were driven out of the earth huts. I was so weak that I thought that I could not get up and walk. An SS-man put a pistol under my ribs, and I did manage to get up indeed. (That SS-man saved my life, though that was certainly not his intention.) Prisoners able to walk were driven out of the camp. Later we learned that the Nazis used flame-throwers to kill the many inmates still alive in the earth huts.

A section of the electrified barbed wire fence had been cut away, and we were driven to a rail siding where empty freight cars were waiting for us. It was in the middle of the night; searchlights from guard towers lighted the area. There was wild chaos, SS-men shouting to hurry up, there was shooting, and guard dogs were barking. I was quite scared that we would be machine-gunned inside the cars. I found a flat piece of iron, and Tommy and I managed to be some of the last ones to be pushed into the car. As the door was being slid shut I jammed the iron so that the door did not close all the way. While the guards were trying to push it shut the train was starting to move. It was still dark outside.

The train went but for a short while when American fighter planes attacked it. The train came nearly to a halt, and the planes kept shooting it up. There was still snow on the ground, it had been a hard winter, and these were the foothills of the Alps. I pushed Tommy out through the door opening, and jumped after him. The train was on an embankment. We landed in deep snow, and fell behind a big tree. The planes kept shooting; but the tree was protecting us. We were on the shadow side of the bullets. Other inmates who jumped from our car were hit, some fatally so.

Fred and his friend Tommy struggled to their feet, and decided to walk east through open fields, hoping to find a barn or even a haystack to use as shelter. However, they were caught by German troops, who brought them to another section of Kaufering. Ultimately, they were liberated by American troops on April 27, 1945.

Liberation and Repatriation

“When I was liberated I weighed 35 kilos; give or take, 70-odd pounds. I was one of those shuffling skeletons you’ve seen in pictures. I said, I didn’t have lice, lice had me.” He was hospitalized for a long time and returned to Prague as a repatriated Czechoslovak citizen.

Fred describes the transition immediately after the war on his website:

The US Army had emptied for us a small sanatorium, a hotel-like building in a near-by spa, Bad Woerishofen, then an enclave of hospitals for wounded German soldiers. A few other survivors and I were brought there, cleaned and bathed. There was food, but I was careful to eat but a little. I knew how dangerous it was to eat after long starvation. There was no medical staff in the building. Sores and wounds were perfunctorily attended to. No other care was provided and some survivors died there.

Fred regained some of his strength and weight and was eventually, with other survivors, taken by truck and train back to Prague.

Arriving to Prague

He immediately went to his family’s agreed-upon meeting point, the concierge of the building where they had lived. Fred was the only one of the family to do so, the sole survivor. He learned from the concierge that the family’s apartment had been taken over by a Nazi official. When confronted, the new occupant yelled angrily, hurling insults at Fred and boasting of his powerful connections in the new government. Needless to say, Fred was unable to regain control of his former home.

A family friend had also come to the concierge to inquire about the family, and had left her address. Fred, still in poor condition, went there – fortunately it was not far – and she gave him space in her home.

Stella

In 1946, Fred married the neighbor who had taken him in after the war. Her name was Stella Horner and she was his girlfriend before the war and at Terezín. When Fred was strong enough to work, he took a job in an office, and then in a film studio.

“Stella is a sad, sad chapter in my life,” recalled Fred. “She was a wonderful person, decent, everything you can ask for, except that she was very, very much affected by the war. She had all the symptoms of a survivor, bipolar, depression. Today we have names for that, post-traumatic whatever. She was hospitalized on and off.”

To Paris

“In 1946, soon after we got married, I decided that Prague was going to go Communist, and I didn’t want to. I escaped with false papers to Paris, with Stella.” While in Paris, Fred studied art at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and the Académie Julian briefly, though beyond that he was mainly self-educated.

“In Paris the winter of [19]46-47 was pretty bad. I had a friend in Beaulieu-sur-Mer, which is near Nice, on the French Côte d’Azur, who invited us to come for a visit. Paris was cold and hungry. We went down there, stayed for a short time, and returned to Paris.” While in Paris Fred met Ruth Baeck – the granddaughter or grandniece of Leo Baeck – who was a friend of Stella’s. When she learned that Fred was looking for a job, she told him that the Joint Distribution Committee, for whom she worked, was in need of bookkeepers.

Fred’s knowledge of bookkeeping was limited to some elementary principles that his father had shown him. Nonetheless, Fred went to their office and presented himself as a bookkeeper. The manager asked him a technical question, and Fred improvised a response, completely winging it. The manager’s assistant validated Fred’s answer. “I didn’t know what he was talking about,” recalled Fred, “he was talking gibberish. And I got to be a bookkeeper.”

Fred worked for the JDC from 1947 to 1949. He became an assistant to a woman who handled finances for Aliyah Bet. “There was a man in Paris, an important man at the Joint Distribution Committee, Charles Passman who was instrumental in arranging for the transport, all the big ships that were smuggling people into Israel. All the lists of these big transports went through my hands. So that was my little finger in history. I was a tiny little wheel in that big machinery.”

After a humanitarian plane of sick children crashed enroute from North Africa to Sweden, killing nearly everyone on board, Fred said, “That did it for me. I said, ‘I can’t do it anymore.’ I decided I have to get out of the immigration business.”

To New York

In 1951, Fred and his wife left Paris for New York. Enroute, they spent a year in Canada, first in Toronto and then in Montreal. “I always knew I wanted to move to New York. Stella had two uncles here, and one of their sons became quite a successful businessman,” Fred said. “When we arrived here, they didn’t know what to do with us. They were of no help whatsoever. Luckily I didn’t need it by then; I was skilled enough to take care of myself and Stella.”

When Fred and Stella arrived at Grand Central Station from Montreal, there was no one there to meet them at the station. That did not faze Fred. “I knew enough about New York by then, I knew exactly where the subways were running, I spoke enough English. I had written to a friend of Stella’s to get us a room, just to start out with.” The room turned out to be a dismal place in terrible condition.

The couple refused to move in, and instead took a room at the Hotel Paris on West 97th Street. Fred found a job and found an apartment on West End Avenue at 101st Street. The building had converted some small servant rooms on the roof into tiny apartments, so the couple had a penthouse apartment. “To this day I say, ‘I arrived in New York with suitcases; six weeks later I lived in a penthouse on West End Avenue.’” In the late 1960’s, the couple moved to a place on the Upper East Side, one of the few wooden houses in Manhattan.

Becoming an Artist

Fred Terna (photo credit: Daniel Terna)

Fred’s interest in art began early in his life. He writes on his website:

As early as 1943, while still in Theresienstadt, I decided that I wanted to become a painter. In 1945, after liberation, then still hospitalized, a friendly soul gave me watercolors and I painted scenes remembering Auschwitz and other places. I quickly realized that part of me was still in the camps, and I changed to painting landscapes. Much later, looking at some of my landscapes I noticed that there were walls and fences in many of them. It taught me that the memory of the Shoah was a part of me, and that it would not go away, and that I would have to live with it.

“I should have gone back to school, but I couldn’t because of Stella, I was afraid to leave her alone. I became a painter, that was one way of being around and involving her in whatever I was doing. And she was a fine painter herself.”

Eventually the couple separated, and Stella died soon thereafter of breast cancer, the signs of which she had neglected. Fred was the one who insisted she see a doctor after she showed him a spot on her breast.

Rebecca

“In 1982, I went to a meeting at the Waldorf of the second generation survivors. There were literally hundreds of second-generation people. On the way back I felt miserable. There I was, coming from all these comparatively young people.” Returning home on the subway, Fred recognized a woman who had been at the meeting. He approached her and invited her to have a coffee with him. He and Rebecca Shiffman – herself a child of survivors – were married several months later and their son Daniel was born in the mid-1980’s.

Fred Terna is internationally recognized as an artist and a scholar. His art is often shown in galleries in solo shows, and he has lectured at the New School in Manhattan and to audiences throughout the United States on such topics as religion, art history, and the Shoah. His memoires are contained in the Heschel Archives (https://www.heschel.org/holocaust-commemoration-committee/archives). He maintains a sunny disposition and positive outlook, “I consider myself a happy person, with a wonderful wife and promising son, a community I am comfortable in and a job I like.”

On his website, Fred Terna writes about being a survivor of the Holocaust:

I’m aware of it every second of my life: inside of me there is a crazed double bass playing an unpredictable tune. Over the years I have learned to play a fiddle above it so that there should be some harmony to my life.