A boy at Theresienstadt: Remarkable story of survival told in new memoir

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has in its collection a beautifully written, heartbreaking letter from Margaret Gruenbaum, who survived imprisonment at the Terezín concentration camp along with her son, Michael, and daughter, Marietta.

“We do not know yet how the future will shape up for us,” says the letter, written after the war, in May 1945. “None of our old friends are alive anymore. We do not know where we are going to live. But somewhere in the world there is still a sun, mountains, apartments, books, small clean apartments, and, perhaps, the rebuilding of a new life.”

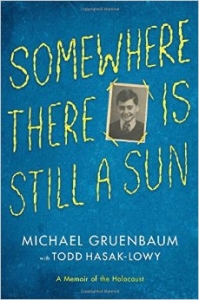

Michael Gruenbaum.

Michael Gruenbaum donated the letter to the museum along with a scrapbook his mother kept containing nearly every piece of paper she received at Terezín. It includes ration cards, Jewish yellow badges and, most importantly, the last canceled deportation order that kept her and her children from being shipped “east” — likely to Auschwitz.

Gruenbaum, an MIT and Yale graduate who has written about child survivors of Terezín, entered the concentration camp in 1942 at 12 and left around age 15. He has just released a memoir based on his boyhood, written for teenagers in first person from the perspective of himself as a young man. Co-written by Todd Hasak Lowy, Publisher’s Weekly called the book “an inspiring testament to human resilience.”

The title? “Somewhere There Is Still a Sun.”

Murry Sidlin, founder and president of the Defiant Requiem Foundation, spoke with Gruenbaum recently by phone. Gruenbaum told of the stories and characters that made their way into the book, including the family’s last deportation order and how a Teddy bear provided an improbable, astonishing way for his mother to keep them off the train. What follows is an edited, condensed version of their conversation.

Murry Sidlin: Having lived in Prague, had you come across the name of the town, Terezín, before?

Michael Gruenbaum: All our Jewish friends were being sent away, and I think I probably knew that the name Terezín was mentioned, but we didn’t quite know what it was. Before the war, no, I had no idea about Terezín.

Sidlin: I met a pianist some years ago, Edith Steiner-Kraus, who told me that her years in Terezín were some of the best years of her life because she never felt more useful as a musician as she did there. You made a statement that you were actually happy to be sent to a concentration camp. Can you explain that for us?

Gruenbaum: Life in Prague after the Nazis came — every day was worse and worse. We had to wear a yellow star on our clothing, and that meant if I dared to go outside of our apartment, bands of kids were chasing me and pelting me with stones and things like that, so that was not very pleasant.

Before the war, we had a large apartment in one of the most modern buildings in Prague. As I mentioned, my father was a fairly prominent attorney. He could afford a car, which is something that people could not afford at that time. We had a cook, we had a governess, and we had a good life. But when the Germans came, we were forced to abandon that apartment. We were forced to get rid of all the help that we had.

We had to move into a small apartment in the Prague ghetto, and we were not allowed to attend school. We were not allowed to go to the movies. We couldn’t go to concerts. We were not allowed to play in the parks. We had to sit in the back of streetcars. We were not allowed to travel outside Prague, and we had to turn in all the jewelry and artwork and radios, skis and bicycles and musical instruments. We had all our bank accounts confiscated. Parents were not allowed to work. We were not allowed to associate with any non-Jewish friends. We could buy groceries only at certain times of the day, like from 3-5 on certain days, and we were allowed to buy only certain groceries. So, life was horrible. I thought to myself, well, if we are going to go somewhere, maybe it’s much better there.

We had to move into a small apartment in the Prague ghetto, and we were not allowed to attend school. We were not allowed to go to the movies. We couldn’t go to concerts. We were not allowed to play in the parks. We had to sit in the back of streetcars. We were not allowed to travel outside Prague, and we had to turn in all the jewelry and artwork and radios, skis and bicycles and musical instruments. We had all our bank accounts confiscated. Parents were not allowed to work. We were not allowed to associate with any non-Jewish friends. We could buy groceries only at certain times of the day, like from 3-5 on certain days, and we were allowed to buy only certain groceries. So, life was horrible. I thought to myself, well, if we are going to go somewhere, maybe it’s much better there.

Sidlin: In many stories of people who survived the Nazi era, almost everybody thinks back to one person who was influential, inspiring, or enormously helpful, even sometimes at personal risk. You mentioned someone by the name of Franta, who was apparently someone who was very important to you and the other boys who were in your group. Tell us a little about who he was, how you met him and what he meant to you.

Gruenbaum: When I arrived at Terezín, I got my first strike right away because I was separated from my mother, and they immediately put me into this room — room seven — with 40 other boys. There was this young boy, although he seemed much older than we were, but he was only 20 years old and we were 12.

He instilled fear in us early. He didn’t take any nonsense from anybody. But on the other hand, he insisted on teaching us everything he could. He taught us about music, he got some people in to teach us about history and geography. He helped us with writing a magazine. So he tried everything he could to keep us out of trouble but also to keep the morale up. It was just an incredible performance of a 20-year-old to be thrust into that role.

There were other rooms, and they each had a madrich. What distinguished Franta from all the others was not only that he survived — some of them did not — but the others didn’t do what he did, which was after the war, he kept track of us. After our reunion in 1989, he kept calling each one of us, no matter where in the world we were. He kept calling us every other week, trying to find out how things are and so on. He did that through the end of his life. It was amazing. We became his children.

Sidlin: Tell us about the Teddy bear and what it meant for your survival.

Gruenbaum: The worst thing in Terezín was the fear of being in a transport. Nobody knew where the transports were going. We were told they were going east, and that’s about it. And then later on we found out that going east meant going to an extermination camp, most likely Auschwitz, but we didn’t know anything about that.

My mother developed a code with her sister-in-law. If one of them were deported, and were able to send a note or some kind of postcard or letter, if the handwriting was going up, that meant the other place was better than Terezín, and if it was going down, that meant it was worse. It turns out that my aunt was deported, and she was one of the few people that were still able to send a postcard to my mother. She said she was already working as a seamstress — of course, she never worked as a seamstress before — and the handwriting was going down, so we knew something was up, which was not good. So my mother tried to do everything she could to keep us in Terezín.

For the first couple of times we were summoned to go on the transport, my mother was able to get us out by reminding the people who were making up the lists that my father had done a lot of good things for the Jewish community in Prague, and so they pulled us out of the transports. But the last time, which was in October of 1944, it was very difficult to do that because the people who were making the lists were themselves being deported. There was nobody to go to. In this transport queue that we were in, we were called to the assembly area, and our number was 1,350 or so out of 1,500. That gave my mother one more chance to pull a rabbit out of the hat, so to speak.

We went to the assembly area, and because we didn’t have to board the train right away, she went over to where she worked, which was the arts department. She talked to her boss, who was Jo Spier, the famous Dutch artist, and she told him, ‘Listen, that order that the SS man gave us to make those Teddy bears for his children for Christmas won’t get filled, because I’m being deported.’ So he immediately went to the SS man and told him that, and the SS man said, ‘All right, why don’t you pull her out.’ And Mr. Spier said, ‘Well, she has two children, if they go, she will go with them.’ So he said, ‘OK, pull them out as well, but nobody else.’

We got a little slip of paper saying we were being pulled out, and she came rushing over to the assembly area and told us to follow her. We went to the registration desk and presented that little piece of paper, and that’s what got us out, except that’s not really the end of the story.

They told us, ‘You can’t leave yet. You have to go up to the second floor and wait for the train to leave.’ We had to move upstairs. We opened the door to the first room, and it was completely filled. We couldn’t get in. We went to the second room, and that was filled, so we finally ended up in the third room, which was farthest from the stairway, and that’s where we were able to wait for the train to leave. Everything was working normally, and then suddenly there was a big commotion, and soldiers were rushing up the stairs. They said they had to get 50 more bodies. They got everybody out of the first room, they got half the people out of the second room, and luckily they never came to the third room. That’s why I am here today. That’s how the teddy bear saved us. That, and luck.

Sidlin: Do you remember liberation day? Not that the war was over, but when you were able to leave Terezín?

Gruenbaum: It was liberated by the Russians. I had a friend — one of the older boys, I think he was one year older. His father had something to do with the horses. He kept the German’s horses in good shape, because that’s what he knew how to do. When we were liberated, my friend and his family got a cart and two horses, and they just drove away to Prague, and they took me with them.

I think we went through the whole night, about eight hours or something. My mother and my sister, unfortunately, weren’t unable to leave because right after that, they closed the doors, so to speak, because of typhoid fever that came from people who came from the death marches. So they couldn’t leave until the end of the month. I stayed with his family for three weeks or so. Then my mother and sister came, and they were able to get an apartment for us, and I joined them again.

Sidlin: When you think back to all of this, does it seem real at age 85? Not only was it a long time ago, but it was a great lesson in what people can become — what the Nazis were and how they acted, and the darkness of the human spirit and what it can be. Do you think about these lessons from the Nazi era?

Gruenbaum: Well, as you can see, I have never forgotten them. I think it’s ridiculous that I’m here because of a stuffed Teddy bear. I just can’t get over that. Somebody asked me, ‘What lessons have you learned from all of this?’ And I say, well, probably two things.

One, I learned to persevere. Just don’t take no for an answer, which is what my mother learned, and what she taught me. The other thing is that possessions don’t mean anything. They can be taken away, and they can be replaced. Those are the two major things I keep telling my kids.

Michael Gruenbaum lives in Brookline, Mass.

To order a copy of Somewhere There Is Still a Sun: A Memoir of the Holocaust, click here.